For a director fresh from the Palme d’Or at Cannes and in the running for the Oscars, sitting in a hotel room answering questions from the press should be normal. However, Jafar Panahi, whose life and career have been inexorably hindered by the whims of the Iranian regime, is not. After the victory in Cannes, Panahi was able to present A simple accident in person at the Telluride and Sydney festivals and then at the Rome Film Festival, in a moment of unusual relaxation of the grip that his country’s government has always had on him. From 2010 to today, he has achieved a cinematographic record achieved only by him among living filmmakers, namely that of winning the three great festivals of the Old Continent: Berlin, Cannes and Venice. Often, however, his films were shown at these festivals in his absence.

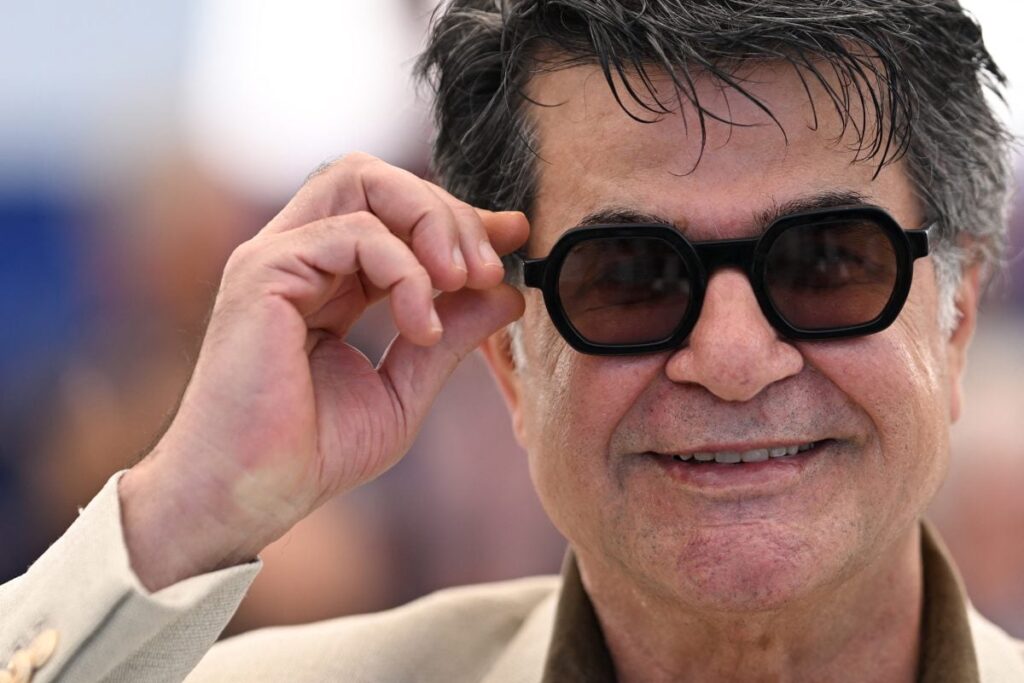

Especially since 2010, when the Iranian government first prohibited him from traveling and then from making films: a ban promptly ignored by Panahi. A ban that shaped his subsequent films, sometimes shot in semi-clandestine conditions, and which forced him to take advantage of limitations and denials (his own, his incarcerated colleagues, his acquaintances and friends thanks to whom he put together films like Bears don’t exist e Taxi Teheran) to make great cinema. In July 2022 this small man, with his gaze always hidden behind a pair of square sunglasses, who as I speak to him sinks into a golden sofa in the room of a Roman hotel, sat in a cell in Evin prison, together with other Iranian political dissidents. There he spent six months, until, after a hunger strike and the international mobilization of the cinema world, he was freed.

Outside those walls he brought with him a skein of emotions, encounters and reflections that took him time to unravel, transforming them into the narrative lines of A simple accident. A film born behind bars, which contains his experience and the stories of those who were in Elvin with him, but which looks beyond: beyond the cell, beyond the regime, to the point of questioning the “after”, how and by whom Iran can be rebuilt. A surprising outcome for a film that starts from a kidnapping – that of an alleged interrogator/torturer of the Iranian military police, recognized by one of his victims and kidnapped by a group of ex-prisoners in search of the truth. The doubt about his identity – is it really him or is it a mistake? – runs through the whole story, together with the confrontation between its victims, who ask themselves the same questions that one day, perhaps, Iran will also have to face.

ⓢ I would like to start from the future. It really struck me how A simple accident look beyond, to tomorrow’Iran, almost taking it for granted that it will be very different from the present, that in a short time the regime will no longer be there. Where does this confidence come from? Whyand make a warning film on what to do after the regime?

That was exactly my intent: with A simple accident I really wanted to make the viewer think about what will happen, when it happens. When the regime is over, and I believe it is a matter of time, an uncertain future will open up in Iran. I wondered whether, once we put an end to Iran as we know it today, this vicious cycle of violence that characterizes it will disappear. I believe it is not a given, on the contrary: there is the possibility that violence will increase but also that the nation will be able to interrupt the infinite return of abuse. There is not just one possible future. However, breaking the cycle of violence is the necessary prerequisite for creating a better future and achieving this must already be thought about now. When that time comes, we must be ready.

ⓢ What kind of spectator did he imagine would receive his warning?? L’the impression is that he wants to extend it beyond the Iranian public, that he also wants to speak to those who live outside of Iran’Irannot only to describe to him what is happening now in the country, in a geopolitical moment which at many latitudes makes Iran less distant, politically speaking.

An artist, when he creates a work, must first of all create what he feels is necessary. This applies to any artistic product: this is my belief. Then, only at a later moment, will he also be able to convince others of his value and stimulate reflection. I believe that stories of this kind always find their audience, because in the world there are always those who know this type of reality intimately. Obviously, those who have no experience of this type of political framework are also involved in this reflection. However, as a filmmaker I believe that one cannot decide at the beginning “this film will be only for Iranians” or “I want it to be aimed above all at foreigners”. I often say that I make social cinema: one of its founding components is that it deals with the humanity of people, and humanity, throughout the world, finds its space to be understood.

ⓢ The way you just described your creative process is very powerful. Many authors talk about the need to tell the public something as the main incentive behind their writing, while you describe yourself only with your idea, busy convincing yourself, forgetful of who will then see your film. It also happened for A simple accident? Did you also think about it in prison, about what the film in which you would translate that experience would be?

Making social cinema, I take inspiration from everything that surrounds me: from the context in which I live, from what I see happening around me. If she were a director here, she would talk about the problems she knows, for better or worse, of this Italian society in which she lives. It’s like this for me too: I know my country, my city, I’m aware of their nature because I experience it every day. When they arrested me and took me to prison for seven months, everything I saw in there inevitably influenced me. At that moment I wasn’t thinking of making a film out of it, no. Once outside, all the experiences and stories I had encountered stuck with me and inspired me.

ⓢ I allow myself to contradict you. You seem so certain that anyone, in your place, having your aptitude and talent, would have made a film out of your experience in prison. Luckily for me I have no way of verifying this, but if I’m honest, I think that in his place I would be too scared to shoot anything.

It’s a fear that disappears when you start making the film, I assure you. Before you start, when you’ve never been arrested, you feel fear. When you are released, of course, you sometimes fear being arrested again. But once you enter prison and experience what it means to be in a cell, that paralyzing fear vanishes forever. Once you’re on set, you get rid of it.

ⓢ What is autobiographical about his experience in Elvin prison in A simple accident?

Some experiences in the film are modeled on my own — for example the interrogation, which is a common, practically obligatory step for everyone who has been in prison in Iran. Instead, many others come from my cellmates: some had been there for years and told stories that they had heard from those who had preceded them and that they had met during their sentence. When I left, as a director, I saw before my eyes all these characters who embodied the different attitudes I came into contact with: those who wanted to destroy everything for a wrong they had suffered, those who were looking for a non-violent approach and ended up in jail for this. I remember, for example, being very struck by the story of a simple worker who only asked for a fair wage and that was his fault, in the eyes of those who had condemned him. All of them inspired me.

ⓢ Compared to his previous films, here the regime has a face, but above all a body: this time there is a character who embodies the Iranian regime, or at least that’s what the protagonists think. A character who, right from the start, is told in all his human nuances, so much so that he also manages to inspire a certain empathy in the audience.

It’s not about rooting for one side or the other: it’s a narrative technique, a game with the viewer, to take them to the final message. It is deliberately written in this way, to continually keep the doubt alive in the public: is he really one of the regime or not? It is this doubt that fuels the interest of those who see the film. Take the opening, for example. We see that Eqbal causes the death of a dog by hitting it with his car: he is sincerely sorry. However, shortly before he silenced his daughter who was singing and dancing in the back seat, he told her to be quiet, that she wasn’t well, even though they were crossing a long stretch of countryside without a soul in sight. He even does it in a whisper: that’s the typical hypocrisy of people close to the regime. Sitting next to him is his pregnant wife, who says to her daughter, shocked by the dog’s death: “It was an accident, it’s God’s will. God put us in front of this dog to avoid worse events.” This is where the title of the film comes from: this is a very common way of thinking among those who hide behind religion to avoid facing reality.

André Itamara Vila Neto é um blogueiro apaixonado por guias de viagem e criador do Road Trips for the Rockstars . Apaixonado por explorar tesouros escondidos e rotas cênicas ao redor do mundo, André compartilha guias de viagem detalhados, dicas e experiências reais para inspirar outros aventureiros a pegar a estrada com confiança. Seja planejando a viagem perfeita ou descobrindo tesouros locais, a missão de André é tornar cada jornada inesquecível.

📧 E-mail: andreitamaravilaneto@gmail.com 🌍 Site: roadtripsfortherockstars.com 📱 Contato WhatsApp: +55 44 99822-5750