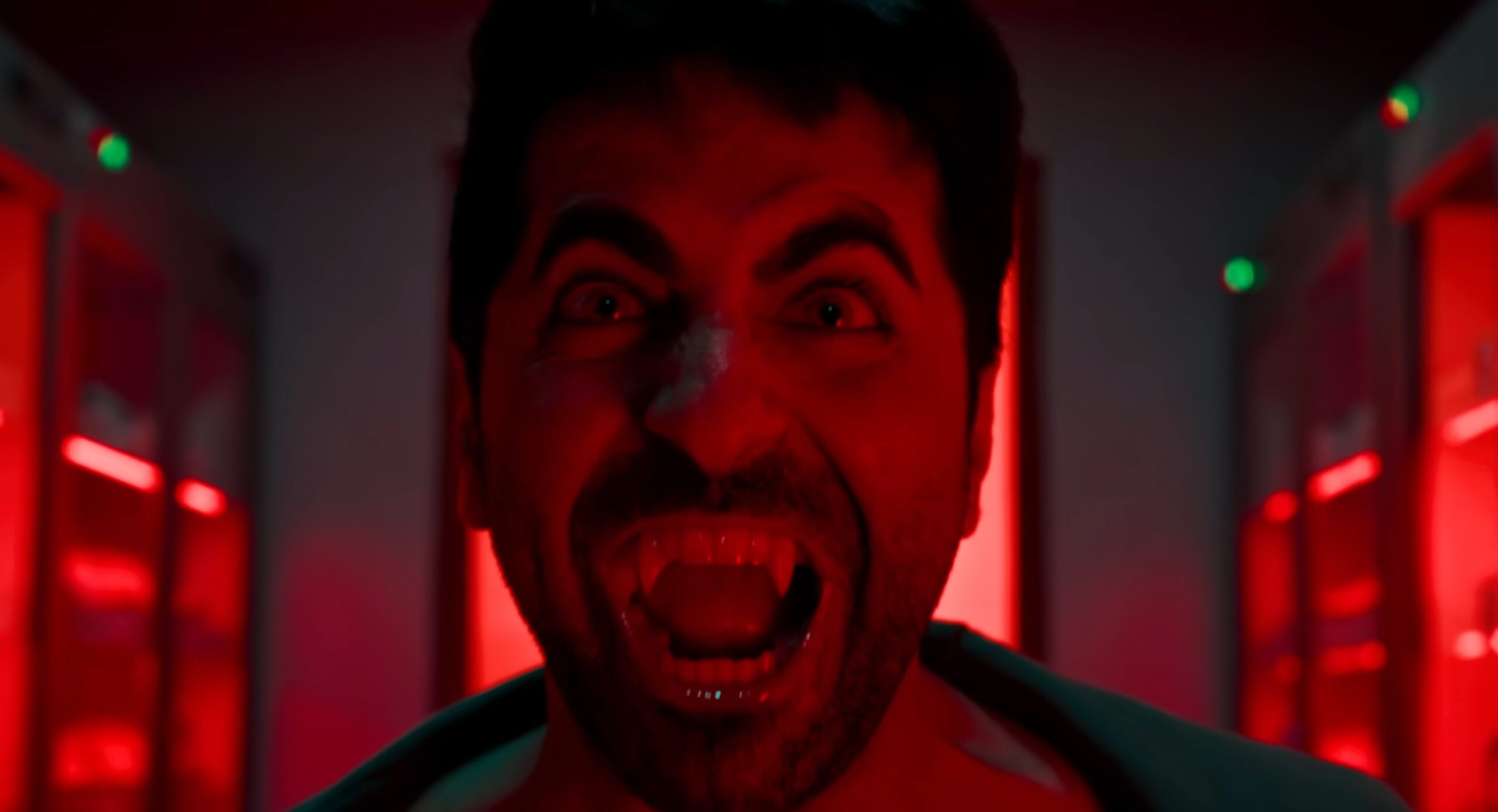

Thamma opens in 323 BC. A cocky Alexander the Great boasts to his troops during his invasion of India. But the fabled Greek warrior does not die in Babylon — he is slaughtered in a tropical jungle by a fanged ‘betaal’ leader named Yakshasan. This bloodthirsty Hindu demon is revising history without even realising it. “You will take over Bharat?” he snarls. Yakshasan spends the next several centuries feasting on anglo blood. He picks up some broken English on the way. India’s independence movement in the 1940s is a buffet for him: pale-skinned and stiff-lipped colonisers everywhere. But Yakshasan is soon debarred and locked up by his own clan when they realise that his freedom-fighting was a front for uncontrollable primal instincts all along. He wasn’t a spiritual protector or paranormal vigilante, just a hateful being out to erase one community. A hammy Nawazuddin Siddiqui playing Yakshasan stokes the narrative fire. The metaphor writes itself, but Thamma refuses to pay any heed to its most interesting character: a power-hungry madman who is exposed for milking nationalistic fervour.

Instead, Thamma chooses the dullest and most vanilla route possible — that of being the latest entry in a homegrown fantasy franchise. Trust a Bollywood entertainer to reduce its best player to a drinks-carrying substitute. As the fifth film of the MHCU (Maddock Horror Comedy Universe) after Street, wolf, Munjya and Street 2, Thamma markets itself as the first love story of the lot: a romcom shaped by vampire-coded folklore, not the other way around. Despite the optics of ambition, it fails on multiple counts. In terms of using comedy as a crutch to stage social horror, it’s the limpest of the five; the humour doesn’t land because it doesn’t commit to the drama. As an Indian adaptation of bat bites and superhero lore, it lags way behind the recent Malayalam hit Lokah Chapter 1: Chandraa near-perfect blend of genre film-making and cultural commentary. And as a love story, there is more chemistry, purpose and magic in the final 15 minutes of wolf than in the whole of Thamma; those 15 minutes featured two wolves and no humans. I’m not fond of comparisons, but to draw from its own central theme, Thamma is cursed by its own vampirism. It flatlines in no time, because it tries to grow feelings without a heart. And the only stakes in the story are the ones that are not driven through the chests of the mythical beings. I also have a dead-on-arrival pun, but I’m going to bury it until the inevitable zombie comedy.

The setting of Thamma trades context for texture. A reporter named Alok Goel (Ayushmann Khurrana) is attacked by a not-so-cuddly bear during a camping trip, only to be rescued by the mysterious Tadaka (Rashmika Mandanna), a male-gaze-clad version of a fierce supernatural entity. A wide-eyed Tadaka is fascinated by the heartbeat she hears in a smitten Alok’s body. He of course falls for her because she’s a mix of subservience and agency: he can mansplain the surroundings to her as well as be saved by her. This interspecies relationship is apparently intense enough for Tadaka to break the rules of her clan, venture into civilisation with him, break more rules, and serve as a clumsy stand-in for an interfaith romance in Alok’s chaste vegetarian household. His dad (Paresh Rawal) is suspicious about Alok’s miraculous return with this girl; not many father-son moments and godfearing-WhatsApp-uncle gags land here. Meanwhile, a shackled and cackling Yakshasan waits for fellow betaal Tadaka to commit a mistake and take his place. As is evident in the trailer, the second half revolves around Alok’s ‘integration’ (a half-witty analogy for religious conversion) and adventures as a wannabe Delhi vampire who’s consumed too many movies to be original.

The world-building of Thamma feels a little like excited writers’ room ideas that don’t go beyond a draft. Given the unfamiliarity of this genre on Hindi shores, the scope is endless. But the focus is more on creativity than subtext; any political nods feel like watered-down draught beer in a Mumbai dive bar. The interplay between actual history and the film’s fictions is not explored enough. The aversion of the community towards humans, which in turn defines the ‘taboo’ bond between Alok and Tadaka, stems from a man-made disaster; this revelation, though, feels like a non-serious and self-righteous punchline. There’s also the fact that the protagonist of the film is actually Tadaka, a character who puts her heritage on the line for a love that defies all norms (because the film insists it exists). Yet Alok steals the spotlight because he is a man written by men in a quasi-feminist tale that involves at least two item songs and the death of irony.

This also happens because Thamma is an “installment” rather than a part — one that’s derailed by its forced links to the Street movies, wolf and Munjya. It isn’t allowed to stand on its own, to the extent that the cameos of other MHCU (yes) characters are expanded into lazy plot points and derivative action pieces. When it hits a wall or finds itself having to manufacture momentum, it resorts to its lineage; it’s the cinematic equivalent of a kid who pulls the rich-family card the second he is punished for not doing his homework. The canons are reverse-engineered to connect all films by hook or crook (someone even mistakes Khurrana’s Alok as Bittu, the sideling played by brother Aparshakti Khurana in Street). I could swear that the impressive VFX wolves from wolf get a downgrade too, like a marginalised beast who gets culturally appropriated by the mainland. A shot of blood somehow becomes a key ingredient for all sides, and this doesn’t include my blood-shot eyes in a post-Diwali matinee show.

Another problem with Thamma — other than a nothing-burger (or nothing-kulcha) of a climax — is the uneven tone. It’s hard to invest in the survival of the couple and their battle against all odds when the film itself keeps lapsing into peels of parody. At one point, when Alok is struggling to acclimatise to his new nature, the couple is directed by a fellow clan member posing as a cop to a ghetto blood bar and nightclub, whose low-fi cosplay strays into the territory of Netflix’s Tooth Pari: When Love Bites. There is no reason for the sudden fetishisation and change of scale (except a Nora Fatehi dance), so the film is then obligated to stage a big conflict in this makeshift location. At another point, a gag of Tadaka getting drunk after mistaking red wine for blood (at a bar, you guessed it) is inflated into a warehouse face-off with thugs who exist as sole proof that this film is unfolding in Delhi. A similar piece in Lokah reveals the hidden identity of the woman to an oblivious male slacker, but here it’s just a gimmick to show that Tadaka cannot control her protective impulses and feelings for said slacker; it even defeats her lust for blood. This strange parable of love and sex spells out the difference in gender subversion and game awareness between two languages of cinema. This gap is only cemented when Thamma succumbs to that stale Bollywood habit: When in doubt, Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge. The riff on a famous dialogue works as much as the concept of a North Indian hero who calls for equality after hijacking the love story of the woman who creates him. I know how this sounds. After Baby John and Chhaavayou can’t blame me for spotting an oedipal wife-who-mothers motif from afar.

The performances are nothing to write home about. Khurrana tries to even out the awkward switches between dramatic flair and comic beats, but the cold-blooded writing sinks its teeth into his neck and reduces Alok to a physical medium. Unlike the other films, he doesn’t have a stacked supporting cast either; Thamma’s stubbornness to tell a painfully conventional story in unconventional form leaves him with no room to improvise. Mandanna has a more consistent role and presence, but Tadaka is tempered by the blandness of the film’s spices — the wonder of a goddess rebelling against mythology itself is lost by the time the narrative crawls to an incomplete end. I had to actually wait for the credits to appear to know that it’s over, which is never a good sign for a franchise that is starting to sacrifice individualism at the altar of volume. All we’re left with is the almost-film of Yakshasan, the bored villain who is invisibilised by a legacy that begins with him. Somewhere along the line, I fear he feasted on the blood of an Irish gentleman named Stoker, who was yet to finish a gothic-horror novel called Dracula. The result of this history-altering act in 2025: Thamma.

André Itamara Vila Neto é um blogueiro apaixonado por guias de viagem e criador do Road Trips for the Rockstars . Apaixonado por explorar tesouros escondidos e rotas cênicas ao redor do mundo, André compartilha guias de viagem detalhados, dicas e experiências reais para inspirar outros aventureiros a pegar a estrada com confiança. Seja planejando a viagem perfeita ou descobrindo tesouros locais, a missão de André é tornar cada jornada inesquecível.

📧 E-mail: andreitamaravilaneto@gmail.com 🌍 Site: roadtripsfortherockstars.com 📱 Contato WhatsApp: +55 44 99822-5750