Next Thursday, October 16, it will premiere in cinemas in Argentina Mastermind (The Mastermind), the new film by the notable director of films such as River of Grass (1994), Old Joy (2006), Wendy and Lucy (2008), Meek’s Cutoff (2010), Night Moves (2013), certain women (2016) y First Cow (2019). We spoke with her about her cinema and her most recent film starring Josh O’Connor, Gaby Hoffmann, Bill Camp, Hope Davis, John Magaro and Alana Haim.

Published on 10/11/2025

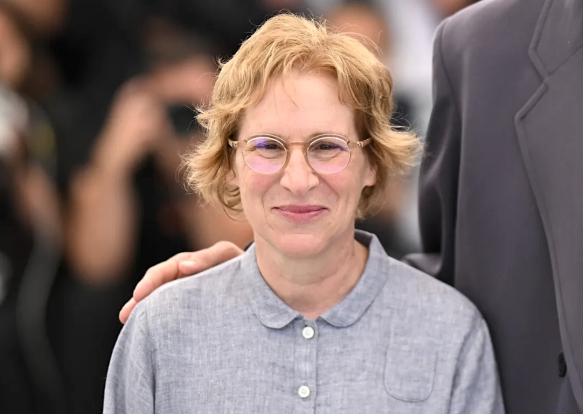

Kelly Reichardt competed last May at the Cannes Film Festival with Mastermind (here our review), strange foray into a classic genre like that of heist movies (heist movies) set in the early 1970s, but – of course – with a very unconventional and decidedly personal approach.

OtrosCines.com had the opportunity to interview Reichardt on the terrace of the Palais de Festivals in Cannes to chat about his brand new feature film.

There is a strong political tension in the film. Did you think about that while you were writing the script and then filming it?

Yes. If you think about the Watergate hearings, it was impressive. Legislators from both parties were crying, there was a real feeling. If you see him today with someone young, they don’t even believe it. They tell you: “EIt’s all a setup“But no, it was an authentic moment. A moment of the country’s loss of innocence. That it even happened seems difficult to explain today. Then came Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, the bank bailouts… And always the United States bombing countries or sending weapons, but with total cynicism, with a general acceptance of corruption. Maybe it seems more honest because the lies are now evident, I don’t know. But seeing that arc, that loss of national innocence, is something impossible to convey to a young student. In my case, I teach at a university and my students only became politically aware during Donald Trump’s first presidency. Trump is the only thing they know. And in the film I focused on a character who is not afraid of being recruited, but who at the same time is destroying his personal world. It is not part of something larger: it is the tension between individual and society that What interests me the most. At the beginning of the film there is a report about students protesting against the silence of the universities. That was in the script before it happened in reality, but now it happens. In that sense, the film seems to resonate with the present, although it was not the initial intention.

And how did the idea of theft from a museum arise in that context?

I read a lot about museum robberies in the 70s. The original seed of the film was the robbery at the Worcester, Massachusetts Museum because it was just celebrating its 50th anniversary and the survivors, teenagers at the time, talked about that experience. The fascinating thing is that most of those works never reappeared. It is incredible to think that a Rembrandt, a Vermeer or a Degas are in some private basement, inaccessible to everyone. But the film is not a heist thriller. It’s more about what remains afterward: the ruins, the echoes. That’s why I was interested in postcards: they are miniature memories of something that may no longer be there. The movie may be grim, but it’s 1970. There were a lot of museum robberies at that time. Today it would be impossible: after the famous robbery at the Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990, where the works were never recovered, everything changed. They added guards, installed security cameras. In the 70s there was no such surveillance. I also wanted to set the story in 1970 because compulsory military service was still in effect. And, to be honest, we filmed in the fall because that’s when I can shoot (in the spring I teach). In the end, filming a story in 1970 is a way of asking how we got here. But I don’t know how to answer. I am confused with the current era. I even remember that three years ago, in Cannes, I said goodbye saying: “I hope we see each other in better days.” Today it seems naive to me. I knew things were going to get worse, but not that bad or that fast. I thought of incompetence, not disappearances. And then Gaza, Biden… I don’t understand the present. The film does not give answers, it only reflects a fragment, a partial and truncated view of the United States.

Cinephile and literary references

Did your love for Jean-Pierre Melville’s films have anything to do with this project?

Well, I love all of Melville’s cinema, but The army of shadows y red circle They are my favorites. I love the way they are composed. They are characters of a different type, right? But anyway, it seemed like fun to do. And I also thought about some novels by Georges Simenon, how he structures things with crime. I kind of often put the crime at the beginning instead of in the second act, where it “should” be. I was also interested in filming a story about the ’70s with the glorious American cinema of that time as a reference.

Performances

There is something very special about how the actors move and speak. How did you work with them?

I come from theater, so I work a lot in rehearsals. Not rigid, but so that the actors feel comfortable. Furthermore, since everything is set in 1970, I wanted the body to express another way of being: how one smoked, how one spoke.

The rhythm of the dialogues is particular, with silences that weigh…

Yes, that’s already in the script, but we delved into it in rehearsals. I didn’t want a fast pace, but rather to leave room for discomfort and stares.

The protagonist seems out of place, not quite belonging to any world.

That fracture interests me a lot: the tension between the intimate versus the historical context. He never manages to integrate, he becomes isolated. That defines the film.

Photography and visual style

I read that Robby Müller’s work in The American friendby Wim Wenders, was a reference. How did you work with your cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt?

It is a very shared work, a constant conversation. We do not start from rigid rules, but from atmospheres, colors, sensations. After First Cow, we saw with Chris Golden City / Fat City, photographed by Conrad Hall, which was just being projected in a theater. It was the first time he had seen her. It was right when we finished this movie. I also had a Polaroid of Robby Müller in my room, a gift from his widow. I sent images to Chris for reference. Watching the finished film, I realize how impossible it is to escape a certain visual tradition. Photographers like Stephen Shore are so assimilated that they are part of our DNA. You look at that time and it is inevitably reflected in the work.

In the film there are very particular camera movements, such as turning around a room. How did that decision come about?

We talk about it, but it’s also intuitive. It’s about how to use time and space. For example, in the postcard scene, I didn’t want to repeat the typical dinner scene with cuts between characters. I wanted to maintain fluidity, move the scene. In the bedroom fight, I preferred a slow approach, getting to the “after” of a moment. The film is a lot about that: about the aftermath, about what remains.

Music

At one point the music is reminiscent of what Miles Davis did for Elevator to the scaffoldby Louis Malle Was it an inspiration?

-If you use trumpet in a ’70s movie, you inevitably think of Miles. But that soundtrack was more romantic. Mine is more avant-garde and experimental. I listened to John Coltrane, Sun Ra and Bill Evans while I wrote. I wanted something minimalist, with a trio. We used the band Chicago Underground as a reference and then worked directly with the trumpeter. He improvised while watching the movie. Then we would edit those improvisations and give them back to him so he could play on them. It was a long process, more artisanal than spontaneous. We finally recorded in Marfa, Texas.

Independent cinema and distribution

You make genuinely independent cinema. How do you think about the relationship between your films and the public?

I never thought about the audience the way mainstream cinema does. I am from another generation and from another background. At first I felt that there wasn’t that much distance between what I was making, an independent film, and what was seen at festivals or in arthouses. It was a whole community. Today everything is more segmented. The mass audience goes one way and a small group of moviegoers goes the other. When I started, that cut wasn’t so clear. There weren’t that many platforms or that much content. And the public that went to see an independent film perhaps also saw a blockbuster and vice versa.

And what does it mean to have a distributor like MUBI?

It’s a relief. They work with sensitivity, they know what to do with a film. Before it was frustrating: you made a film and it was in the hands of someone who didn’t know how to move it. With MUBI I feel that there is a broader audience that can find the film, even if it is not in all theaters. And, most importantly, they don’t think of movies as “content,” which is a word I hate.

And what would you like the viewer to be left with after seeing Mastermind?

I am not looking for conclusions or closed answers. Cinema for me doesn’t work like that. What I want is to open a space: for the film to resonate, even if it is ambiguous. Let someone stay thinking, feeling something. Even if it is a discomfort. If I achieve that, for me the objective is already achieved.

André Itamara Vila Neto é um blogueiro apaixonado por guias de viagem e criador do Road Trips for the Rockstars . Apaixonado por explorar tesouros escondidos e rotas cênicas ao redor do mundo, André compartilha guias de viagem detalhados, dicas e experiências reais para inspirar outros aventureiros a pegar a estrada com confiança. Seja planejando a viagem perfeita ou descobrindo tesouros locais, a missão de André é tornar cada jornada inesquecível.

📧 E-mail: andreitamaravilaneto@gmail.com 🌍 Site: roadtripsfortherockstars.com 📱 Contato WhatsApp: +55 44 99822-5750